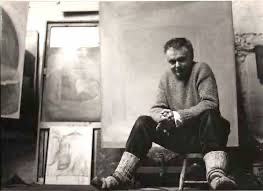

Norman Adams

British

British, (1927–2005)

Norman Edward Albert Adams RA was a British artist, and professor of painting at the Royal Academy Schools. He was married to the English poet and artist Anna Adams (1926-2011)

Norman Adams, the former professor of painting in the Royal Academy Schools, who has died aged 78, said it was his ambition to paint profoundly religious pictures, although he was not a churchgoer and held no particular religious beliefs. He called himself "a sort of freelance agnostic", yet there was always a spiritual intensity underlying his paintings of the natural world, as well as the specifically religious subjects.

Norman's work continued a rich tradition of romantic visionary painting more frequently encountered in Britain than elsewhere. There are close links between his output and that of earlier English painters, such as Blake and Turner. As a young painter, Norman wanted to fuse the qualities of these two great predecessors; although he recognised that Blake never had much feeling for paint, he admired "the poetry and political verse, his intensity and his integrity". Norman also professed a lifelong admiration for the German expressionists, notably Kirchner and Nolde, and the Belgians, Permeke and Ensor. Later in life, it was, perhaps, Van Gogh who most preoccupied his thoughts. Intensity of vision was the bond between Norman and the painters, invariably European, never American, that he cared for.

Born in London, the son of a London Transport clerk, Norman went, aged 13, to Harrow School of Art, from where he won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art (RCA), just before being called up for military service.

He registered as a conscientious objector and spent six "terrifying" weeks in Wormwood Scrubs prison, before winning his appeal against a six-month sentence. This experience convinced him that art had to have a message. "In the broadest sense, you might call it religious. I realised that, for me, art without it would be a pretty empty vocation." In lieu of military service, Norman worked as a farm labourer for two years, before entering the RCA in 1948. In retrospect, he felt the delay helped to clarify his interests as a painter, and by the time he left the college in 1951, he was beginning to form the view that "art was not just a matter of painting objects, but getting beyond objects".He then taught at St Albans art school, and designed decor and costumes for ballets at Sadler's Wells and Covent Garden. But he began to leave London whenever he could to paint landscapes in Yorkshire and Ireland. He came to feel that painters living in cities spent too much time looking over each other's shoulders, and eventually "lose their heritage and are spiritually emasculated".

In 1956, Norman and his wife Anna - they had met as students - bought a cottage at Horton-in-Ribblesdale, in the Yorkshire Dales, where he built a spacious studio overlooking the edge of the Pennine Way and the rising mass of Pen y Gent, often still covered in snow in the late spring. His affinity with the elemental landscape - "there is something pure, clean in the hills and the sea," he said - led him and Anna to the Outer Hebrides; from the mid-1960s, he spent every summer painting on the island of Scarp. Later, a re-reading of Van Gogh's letters - "his life reads like a passion story" - led the couple to Provence, to where they regularly returned each summer.

As a painter, Norman was deeply affected by what DH Lawrence called "the spirit of place". His work combines a poetic and personal vision with acute observation; although he was never a detached observer of nature, he was always able to use visual facts tellingly. The earlier atmospheric water colours of land, sea and sky, of mountains and hills obscured by veils of rain or mist, or sunshine glittering on water, arguably reached their culmination with a show, in 1966, containing larger oil paintings. It was in that year that Norman visited Italy for the first time, to be profoundly influenced by Giotto's frescoes at Assisi and Padua. He also began a series of paintings inspired by religion, mythology and mysticism. These were images containing a complex personal symbolism, and many of those who admired his landscapes and watercolours found such paintings as Crucifixion After Cimabue somewhat esoteric, the symbolism being difficult to decipher.

In the 1970s, Norman produced murals for St Anselm's church, Kennington, south-east London (which he regarded at the time as his major achievement), the ceramic reliefs of the Stations of the Cross for Our Lady of Lourdes Roman Catholic church, Milton Keynes (1975-76), and an even more impressive series of paintings of the 14 Stations of the Cross commissioned for St Mary's Roman Catholic church, Manchester.

In these images of life and death, pain and sorrow, sunshine and shadow, he found a convincing unity between traditional religious imagery and the pantheistic vision underlying his earlier studies of the natural world. Norman was a prolific artist. Apart from his commissioned works, in a typical year he would produce 10 to 12 oil paintings and up to 100 watercolours, which were widely exhibited. His most recent exhibitions were at the Central art gallery, Ashton-under-Lyne, last year, and a retrospective at the Peter Scott gallery, Lancaster University, which is still showing. He held senior teaching posts at Manchester and Newcastle before becoming keeper of the Royal Academy Schools in 1986, and professor of painting from 1995 to 2000. He taught because he felt that it was important for good painters to teach, but also partly from a missionary desire to fight the things he disapproved of, such as the influence of American art, or the increasing bureaucratisation of art schools. He felt strongly that painters should fight to be involved with higher education. Norman said that one of the main factors for his resignation as head of painting at Manchester (1962-70) was because "I found that I was looked on more favourably by the powers if I was running about the corridor with a sheaf of papers in my hand than if I spent time discussing painting with students." He continued teaching as emeritus professor at the RA schools until the effect of Parkinson's disease made his visits too difficult. It was partly his illness that caused him to abandon his larger oil paintings, although he continued making watercolours. The oils had taken on some of the freedom of the watercolours, and he came to believe that "there is nothing you can do in oils that you can't do in watercolours; I don't see a great deal of difference between the two media."

Music and literature were important influences, and his view of nature was perhaps closest to that of Ruskin, who wrote in Modern Painters that "although there was no definite religious sentiment mingled with it, there was a continual perception of sanctity in the whole of nature . . . an instinctive awe, mixed with delight; an indefinable thrill." In Norman's work, there is always this thrill, a sense of exultation, even in death, and a celebration of both bursting life and inevitable decay, a view of creation which is "part-pagan, part Christian".

British

British, (1927–2005)

Norman Edward Albert Adams RA was a British artist, and professor of painting at the Royal Academy Schools. He was married to the English poet and artist Anna Adams (1926-2011)

Norman Adams, the former professor of painting in the Royal Academy Schools, who has died aged 78, said it was his ambition to paint profoundly religious pictures, although he was not a churchgoer and held no particular religious beliefs. He called himself "a sort of freelance agnostic", yet there was always a spiritual intensity underlying his paintings of the natural world, as well as the specifically religious subjects.

Norman's work continued a rich tradition of romantic visionary painting more frequently encountered in Britain than elsewhere. There are close links between his output and that of earlier English painters, such as Blake and Turner. As a young painter, Norman wanted to fuse the qualities of these two great predecessors; although he recognised that Blake never had much feeling for paint, he admired "the poetry and political verse, his intensity and his integrity". Norman also professed a lifelong admiration for the German expressionists, notably Kirchner and Nolde, and the Belgians, Permeke and Ensor. Later in life, it was, perhaps, Van Gogh who most preoccupied his thoughts. Intensity of vision was the bond between Norman and the painters, invariably European, never American, that he cared for.

Born in London, the son of a London Transport clerk, Norman went, aged 13, to Harrow School of Art, from where he won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art (RCA), just before being called up for military service.

He registered as a conscientious objector and spent six "terrifying" weeks in Wormwood Scrubs prison, before winning his appeal against a six-month sentence. This experience convinced him that art had to have a message. "In the broadest sense, you might call it religious. I realised that, for me, art without it would be a pretty empty vocation." In lieu of military service, Norman worked as a farm labourer for two years, before entering the RCA in 1948. In retrospect, he felt the delay helped to clarify his interests as a painter, and by the time he left the college in 1951, he was beginning to form the view that "art was not just a matter of painting objects, but getting beyond objects".He then taught at St Albans art school, and designed decor and costumes for ballets at Sadler's Wells and Covent Garden. But he began to leave London whenever he could to paint landscapes in Yorkshire and Ireland. He came to feel that painters living in cities spent too much time looking over each other's shoulders, and eventually "lose their heritage and are spiritually emasculated".

In 1956, Norman and his wife Anna - they had met as students - bought a cottage at Horton-in-Ribblesdale, in the Yorkshire Dales, where he built a spacious studio overlooking the edge of the Pennine Way and the rising mass of Pen y Gent, often still covered in snow in the late spring. His affinity with the elemental landscape - "there is something pure, clean in the hills and the sea," he said - led him and Anna to the Outer Hebrides; from the mid-1960s, he spent every summer painting on the island of Scarp. Later, a re-reading of Van Gogh's letters - "his life reads like a passion story" - led the couple to Provence, to where they regularly returned each summer.

As a painter, Norman was deeply affected by what DH Lawrence called "the spirit of place". His work combines a poetic and personal vision with acute observation; although he was never a detached observer of nature, he was always able to use visual facts tellingly. The earlier atmospheric water colours of land, sea and sky, of mountains and hills obscured by veils of rain or mist, or sunshine glittering on water, arguably reached their culmination with a show, in 1966, containing larger oil paintings. It was in that year that Norman visited Italy for the first time, to be profoundly influenced by Giotto's frescoes at Assisi and Padua. He also began a series of paintings inspired by religion, mythology and mysticism. These were images containing a complex personal symbolism, and many of those who admired his landscapes and watercolours found such paintings as Crucifixion After Cimabue somewhat esoteric, the symbolism being difficult to decipher.

In the 1970s, Norman produced murals for St Anselm's church, Kennington, south-east London (which he regarded at the time as his major achievement), the ceramic reliefs of the Stations of the Cross for Our Lady of Lourdes Roman Catholic church, Milton Keynes (1975-76), and an even more impressive series of paintings of the 14 Stations of the Cross commissioned for St Mary's Roman Catholic church, Manchester.

In these images of life and death, pain and sorrow, sunshine and shadow, he found a convincing unity between traditional religious imagery and the pantheistic vision underlying his earlier studies of the natural world. Norman was a prolific artist. Apart from his commissioned works, in a typical year he would produce 10 to 12 oil paintings and up to 100 watercolours, which were widely exhibited. His most recent exhibitions were at the Central art gallery, Ashton-under-Lyne, last year, and a retrospective at the Peter Scott gallery, Lancaster University, which is still showing. He held senior teaching posts at Manchester and Newcastle before becoming keeper of the Royal Academy Schools in 1986, and professor of painting from 1995 to 2000. He taught because he felt that it was important for good painters to teach, but also partly from a missionary desire to fight the things he disapproved of, such as the influence of American art, or the increasing bureaucratisation of art schools. He felt strongly that painters should fight to be involved with higher education. Norman said that one of the main factors for his resignation as head of painting at Manchester (1962-70) was because "I found that I was looked on more favourably by the powers if I was running about the corridor with a sheaf of papers in my hand than if I spent time discussing painting with students." He continued teaching as emeritus professor at the RA schools until the effect of Parkinson's disease made his visits too difficult. It was partly his illness that caused him to abandon his larger oil paintings, although he continued making watercolours. The oils had taken on some of the freedom of the watercolours, and he came to believe that "there is nothing you can do in oils that you can't do in watercolours; I don't see a great deal of difference between the two media."

Music and literature were important influences, and his view of nature was perhaps closest to that of Ruskin, who wrote in Modern Painters that "although there was no definite religious sentiment mingled with it, there was a continual perception of sanctity in the whole of nature . . . an instinctive awe, mixed with delight; an indefinable thrill." In Norman's work, there is always this thrill, a sense of exultation, even in death, and a celebration of both bursting life and inevitable decay, a view of creation which is "part-pagan, part Christian".

Artist Objects

Evening, Ashdown Forest 1981.001

Loch Assynt (2) 1990.034